Title of paper under discussion

The Death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: An Epidemiologic Perspective

Authors

Richard H.C. Zegers, Andreas Weigl and Andrew Steptoe

Journal

Annals of Internal Medicine – 2009; 151 (4): 274-278

Link to paper (free access)

Overview

The cause of 35-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s death in the winter of 1791 has ever since puzzled medical musicologists, with theories ranging from deliberate poisoning to roundworm infection from uncooked pork. Richard Zegers and his team present a fresh scientific approach to the evidence, consulting Vienna’s “Daily Register of Deaths” from the winters of 1790-93 to “provide an epidemiological framework into which the observations of contemporary witnesses of his death can be integrated”. Deaths from edema were especially prevalent among younger Viennese men in the weeks surrounding Mozart’s death, a “minor epidemic that may have originated in the military hospital”. The authors suggest the most likely cause of this edema was acute kidney damage, in turn the result of a (highly contagious) streptococcal infection.

Background – some contemporary accounts

Speculation as to the cause of Mozart’s death, which took place at 12:55 am on 5 December 1791 at his home in Vienna, began a week later when “a Berlin newspaper started the rumour that he was poisoned”. Does this diagnosis tally with the evidence? Our authors begin their paper by taking us through some contemporary accounts of Mozart’s final months.

According to some unnamed contemporary witnesses Mozart “may have been ill during a visit he made to Prague (Czech Republic) in September 1791” though Zegers reminds us that “this illness could not have been very serious, because after Mozart returned to Vienna, he completed the score of The Magic Flute (K. 620); visited the spa town of Baden (Austria), where his wife Constanze was taking the waters; and conducted his last completed composition, a Masonic cantata at the opening of a new Masonic lodge in November 1791. In the same period, he composed the clarinet concerto (K. 622) and started writing the score of Requiem (K. 626). His last surviving letter, written to Constanze on 14 October 1791, made no mention of any illness or discomfort; indeed, it depicts a busy life socialising with the composer Antonio Salieri, eating well, and sleeping well”. Mozart’s final public concert took place in the Masonic Lodge on 20 November 1791; he fell ill two days later.

His final illness was described in the closest detail, though 33 years later, by Sophie Haibel, Mozart’s sister-in-law. “She recalled that Mozart’s body was very swollen, which made him unable to turn in bed; that he was conscious and in good mental condition until the last day of his life; and that he was attended by the distinguished physician Thomas Franz Closset (1754 to 1813), who ordered cold compresses for his burning head “after which he lost consciousness and never woke up again.””

A separate account of Mozart’s final days is found in the 1828 biography by Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, Constanze’s second husband. Like Haibel, von Nissen describes Mozart’s final illness as lasting 2 weeks, and he recalls at least one venesection (blood drawing) being performed. Von Nissen “suggests that Mozart’s lifestyle – drinking throughout the day and frequently composing at night – might have contributed to his premature end.” Crucially for our authors’ epidemiological approach, von Nissen “states that many people died of the same illness over this period”. (He also “confirmed that Mozart worked on the Requiem until the last day of his life, singing some parts to his assistant Franz Süssmayr”).

Eduard Guldener von Lobes, a contemporary physician who didn’t himself attend to Mozart but who had spoken to Closset, wrote in 1824 that poisoning was clearly not the case of death, rather a “rheumatic inflammatory fever of a type that was common in Vienna at the time, accompanied by a “deposit on the brain”.”

Another unnamed contemporary witness stated “that Mozart’s finall illness was painful”.

The final contemporary account was Mozart’s own entry in the Viennese Register of Deaths, where the stated cause read “hitziges Frieselfieber” – fever and rash.

“In summary”, writes Dr Zegers, “Mozart’s final illness seems to have been characterized by an epidemic nature, a relatively rapid onset, 2 weeks’ duration, severe edema [swelling caused by excess fluid trapped in body tissues], pain of unknown localization, fever and rash, no dyspnea [shortness of breath] (because Mozart was able to sing parts of Requiem), and consciousness until 2 hours before death. He was also bled at least once.”

Method

Rather than relying solely on these contemporary accounts of Mozart’s symptoms to reach a diagnosis, Zegers and his team also drew on a hitherto underexplored source of evidence – the contemporary Viennese Daily Register of Deaths, published as Verzeichnis der Verstorbenen and housed in the Vienna Town Hall library.

Starting in 1607 all deaths in Vienna were recorded in this register, save for some from high nobility, religious orders and prisons. Cause of death, though not necessarily confirmed by a physician, was given in each case.

Although the months surrounding Mozart’s death – Nov 1791 to Jan 1792 – were most immediately relevant, our researchers sought to put them in context by comparing them with the same 3-month period a year earlier (Nov 1790 to Jan 1791) and a year later (Nov 1792 to Jan 1793).

For the sake of statistical analysis the dead were divided up into three groups: younger men (40 or under), older men (over 40) and women. An assessment was then made to see which groups were dying of which illnesses in which months, to see if any patterns emerged.

Results

Apart from one missing page in the register and 15 names obscured by inkblots, all nine months were successfully analysed.

Out of 5011 deaths, about 2/3 were men and 1/3 women. Men, on average, died younger than women (45.5 years old compared to 54.5 years old).

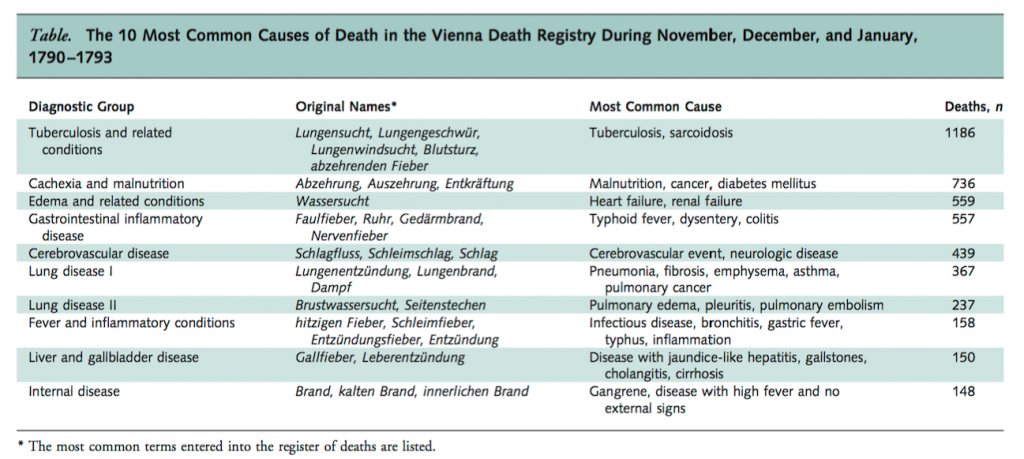

In collaboration with Anton Neumayr, an Austrian expert in historical diagnosis, the authors produced a table detailing the ten most common causes of death found in the Register, grouped under their modern diagnostic names:

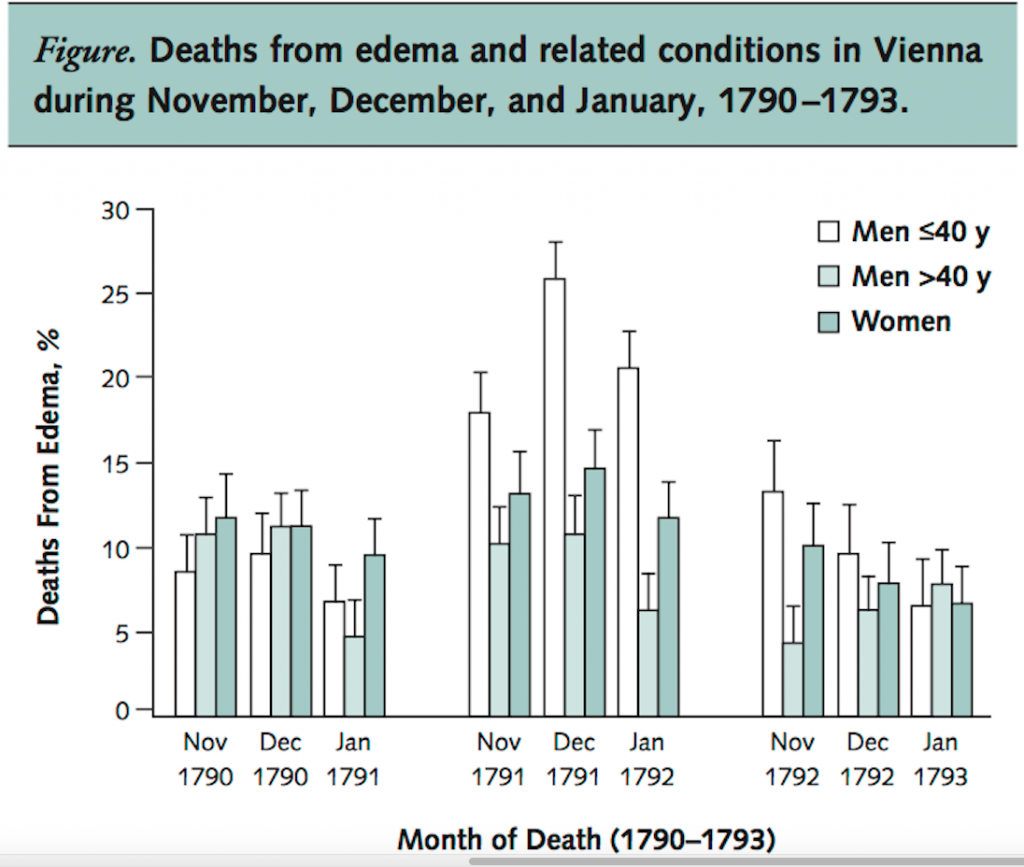

Most crucially for our authors’ investigation, “deaths from edema and related conditions showed a striking increase among younger men during the period surrounding Mozart’s death, compared with the previous and following years” [my emphases]:

None of the other causes of death, when put through the same statistical analysis, showed a similar peak in the winter of 1791-92. Edema was associated with over 25% of the deaths of younger men in December 1791, significantly higher than in other months and than in older men and women. Zegers also provides evidence that “a substantial proportion of the deaths due to edema in the weeks surrounding Mozart’s death took place in the military hospital.”

Discussion

Zegers and his team open their discussion by reiterating that “in the months surrounding Mozart’s death, edema and related disease was the only diagnostic group that showed an increased incidence among younger men. Because contemporary information suggests that Mozart’s death was due to an epidemic condition over these months, the cause of his death might be in this category.”

Despite their inevitable concerns about drawing conclusions from data and diagnostic language that are two centuries old, the authors are confident enough to assert that “our analysis suggests a minor epidemic in deaths involving edema around the time of Mozart’s death. This probably originated in the military hospital. Streptococcal infection leading to post infectious glomerulonephritis [a type of kidney damage] is a possible cause of death involving edema under these circumstances.”

Referencing the contemporary account of Eduard Guldener von Lobes – “In the autumn of 1791 he [Mozart] fell ill of an inflammatory fever, which at that season was so prevalent that few persons entirely escaped its influence.” – Zegers suggest this would match a diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngitis [‘strep throat’], an infection that can go on to cause kidney damage, and hence edema.

We are reminded that diseases other than streptococcal infection can underlie edema, but these tend to be either chronic (e.g. a heart condition) which doesn’t seem likely given Mozart’s musical output in the months leading up to his death, or non-life-threatening (e.g. rheumatic fever).

Patients suffering from the type of kidney damage (called post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis) that can follow on from a streptococcal infection present with “headache and generalized symptoms, such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, malaise, and back pain. Edema [….] is a hallmark of the disease.” This leads Zegers to conclude that “the known facts of Mozart’s fatal illness, including the features of edema, malaise, and back pain, seem compatible with this diagnosis.”

Two more diagnostic possibilities are argued against in the authors’ final paragraphs:

1. Scarlet fever. Though scarlet fever “was associated with deadly epidemics in the 18th century, and the incidence of subsequent glomerulonephritis was apparently high” its associated rash is present from day one of the illness. Mozart’s rash was not described by any of his carers, seemingly appearing only at the very end of his illness – a progression much more typical of streptococcal infection than scarlet fever.

2. Infective endocarditis [infection of the heart]. Though most of Mozart’s symptoms match a diagnosis of this heart condition, the researchers declare it unlikely as edema is a late and rare symptom of infective endocarditis, which anyhow it is not an epidemic disease.

In the authors’ final words:

“our analysis of the registry of deaths in Mozart’s Vienna highlights the possible role of a minor epidemic condition involving edema that primarily affected young men. This, together with the evidence from contemporary witnesses, could fit a streptococcal epidemic leading to an acute nephritic syndrome [kidney damage] caused by post streptococcal glomerulonephritis”.

Coda

‘Lacrymosa’ from Requiem in D minor, K. 626 – W A Mozart (1756-91)

Lucerne Festival Orchestra, cond. Claudio Abbado