Title of paper under discussion

When That Tune Runs Through Your Head: A PET Investigation of Auditory Imagery for Familiar Melodies

Authors

Andrea R. Halpern and Robert J. Zatorre

Journal

Cerebral Cortex, Vol. 9, No. 7, pp. 697-704 (Oct 1999)

Link to paper (free access)

Quick summary

Here are four of this paper’s most important conclusions:

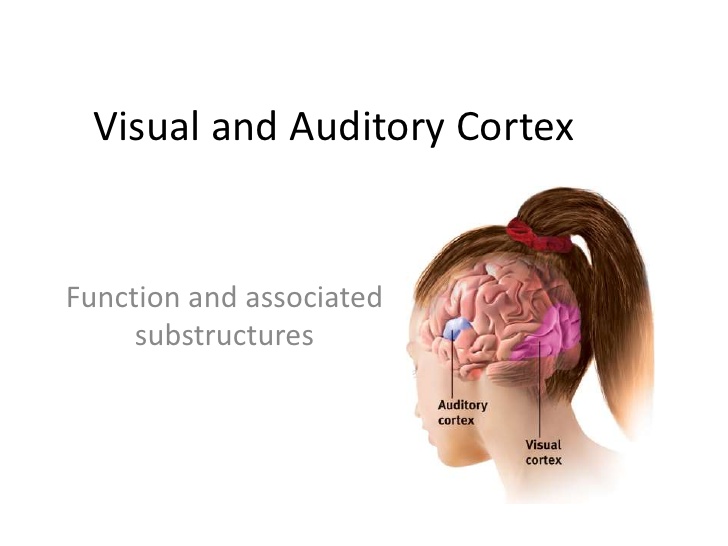

1) Just as visual imagination excites visual cortex (the brain area processing ‘real’ vision), auditory imagination was found to excite auditory cortex (the brain area processing ‘real‘ sound). But whereas visual imagination often involves primary visual cortex, the brain’s starting point for ‘real’ visual processing, auditory imagination in this experiment involved merely secondary auditory cortex, a brain region underpinning ‘down-the-line’, but not the first stages of, ‘real’ auditory processing.

2) Unlike previous studies into imagining songs – which had found activity in the left and right hand sides of the brain – these researchers used wordless tunes (e.g. Beethoven Fifth or “Dallas” theme tune), and found activation mainly on the right side of the brain, strengthening the theory that verbal processing is more left-brained and musical processing more right-brained.

3) long-term verbal ‘semantic’ memory (eg knowing the names of colours, capital cities etc) is commonly reckoned to be a left-brain function; but this paper’s results suggest that musical semantic memory (eg knowing a familiar tune) is more right-brained.

4) The Supplementary Motor Area, responsible for movement coding, is involved in musical imagination – is, the authors wonder, pretend-singing taking place when you imagine a tune?

Overview

Using Positron Emission Tomography (PET) to scan for brain activity, Halpern and Zatorre asked listeners in the scanner to undergo three experiments. In Experiment 1 they were asked just to listen to an unfamiliar tune. In Experiment 2 they heard the opening of a familiar tune (eg the ‘Dallas’ theme tune) and were then asked to imagine its continuation. And in Experiment 3 they listened again to an unfamiliar tune and were then asked them to imagine its repetition.

In a bid to work out which parts of the brain were responsible for particular activities – retrieving a familiar melody (from long-term ‘semantic’ memory), retrieving an unfamiliar melody (from short-term ‘working’ memory), and imagining a familiar/unfamiliar melody – the authors compared the scans from expt 1, expt 2 and expt 3, variously ‘subtracting’ the brain activity present in one from that in another, reasoning that:

1) ‘scan 2’ minus ‘scan 1’ would reveal the brain activity behind retrieving a familiar melody (from long-term ‘semantic’ memory) plus imagining it.

2) ‘scan 2’ minus ‘scan 3’ would reveal the activity behind retrieving a familiar melody (from long-term ‘semantic’ memory).

3) ‘scan 3’ minus ‘scan 1’ would reveal the activity behind retrieving an unfamiliar melody (from short-term ‘working’ memory) plus imagining it.

By making these comparisons the authors were able to suggest that: 1) the retrieval of musical long-term semantic memory largely involves areas in the right Frontal Lobe and ‘secondary auditory’ areas in right Superior Temporal Gyrus 2) the retrieval of musical short-term working memory is based more in the left Frontal Lobe, and 3) imagining a melody, whether familiar or unfamiliar, involves the Supplementary Motor Area.

Introduction

The difference in brain activity between the act of performing and the act of imagining has long intrigued neuroscientists. Most research pre-dating this paper had focussed on visual imagination, revealing that it commonly engages all areas of the visual cortex, and is processed on both sides of the brain (the left perhaps more when the visual images are nameable, and the right more when they are complex).

Research on patients with brain damage had shown that musical perception and imagery both rely more on the right Temporal Lobe of the brain than the left. Further research using Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanning revealed many different brain areas ‘lighting up’ whilst people carry out musical imagination tasks; but such tasks involve many different steps, including long term ‘semantic’ recall and short-term ‘working memory’, so it wasn’t clear which brain areas were exactly responsible for what.

Halpern and Zatorre addressed this lack of specificity by coming up with a 3-part experiment designed to tease apart three different strands of brain activity involved in musical imagination: semantic retrieval (of a familiar tune), working memory (of an unfamiliar tune) and image generation. The three experiments (see Method below) involved the participant 1) imagining the continuation of a familiar tune 2) listening to an unfamiliar tune, and 3) imagining the repetition of an unfamiliar tune. A comparison of the brain activity induced by each of these tasks would variously reveal, reasoned the researchers, the brain areas responsible for musical semantic retrieval, musical working memory and generation of musical imagery.

[In order to investigate brain activity specifically associated with musical processing they decided to work with non-verbal tunes, noting that verbal processing (including verbal semantic retrieval) tends to be a left-brain activity, whereas musical processing is more right-brained.]

Method

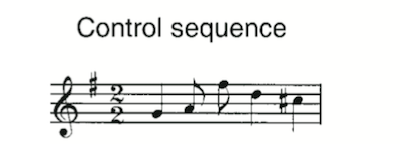

Eight volunteers, all musically trained, each underwent a three-experiment session in a PET scanner. In the first experiment (called ‘Control’) the participant simply listened to an unfamiliar melody.

In the second (called ‘Cue/Image’) they listened to the opening few notes of a familiar melody and were asked to continue that melody ‘in their head’.

In the third (called ‘Control/Image’) they listened again to an unfamiliar melody and were asked to repeat it ‘in their head’.

Results

As outlined in the ‘Overview’ above, the authors compared the scans from expt 1 (‘Control’), expt 2 (‘Cue/Image) and expt 3 (Control/Image’), variously ‘subtracting’ the brain activity present in one from that in another. Taking the comparisons one at a time:

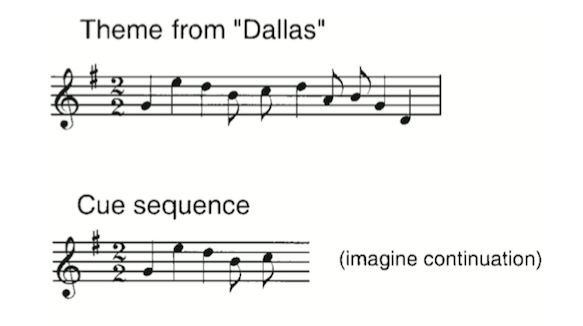

1) The comparison ‘Cue/Image’ scan minus ‘Control’ scan would, reasoned the authors, reveal the brain activity behind retrieving a familiar melody (from long-term ‘semantic’ memory) plus imagining it.

Here is that brain activity:

The areas ‘lighting up’ here include the Inferior Frontal Gyrus (Inf F), an area of ‘secondary auditory cortex’ in the right Superior Temporal Gyrus (STG), and the Supplementary Motor Area (SMA). Most of this activity is on the right side of the brain.

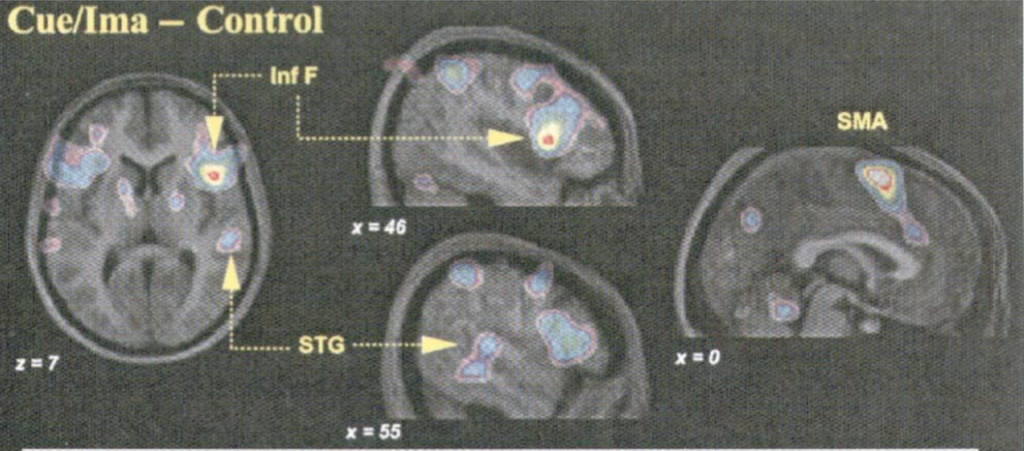

2) ‘Cue/Image’ scan minus ‘Control/Image’ scan would, reasoned the authors, reveal the activity behind retrieving a familiar melody (from long-term ‘semantic’ memory).

Here is that brain activity:

The areas lighting up in this comparison were similar to ‘Cue/Image minus Control’ above [including the right Inferior Frontal Gyrus (Inf F) and an area of ‘secondary auditory cortex’ in the right Superior Temporal Gyrus(STG)]. But note there was a difference: no activation of the Supplementary Motor Area.

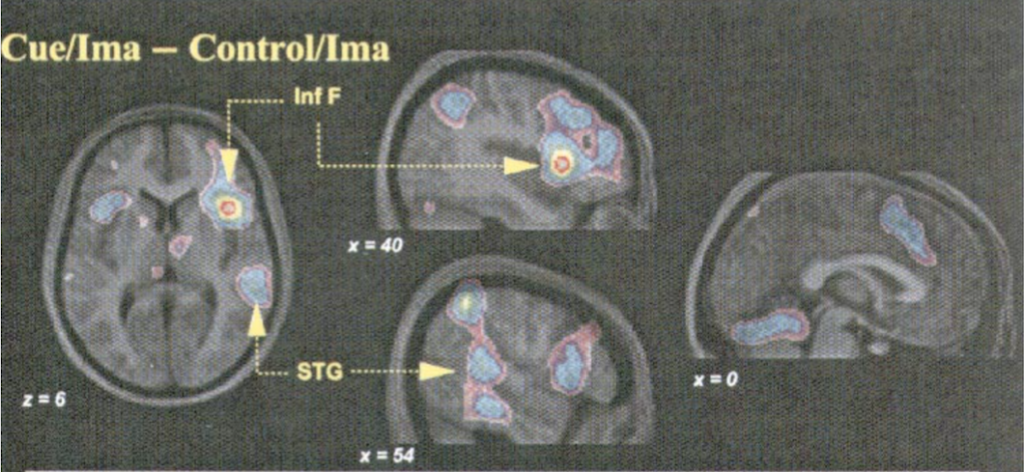

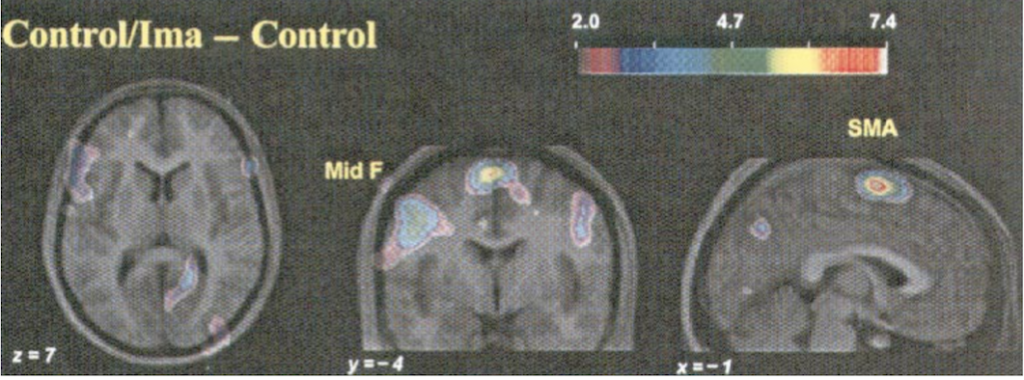

3) The comparison ‘Control/Image’ scan minus ‘Control’ scan would, reasoned the authors, reveal the activity behind retrieving an unfamiliar melody (from short-term ‘working’ memory) plus imagining it.

Here’s that brain activity:

Notably lighting up here is left Midfrontal Cortex’ (Mid F) and, as in the ‘Cue/Image minus Control’ comparison, Supplementary Motor Area (SMA).

Discussion

Breaking the tasks down into their various components (semantic musical retrieval, working musical memory, and generating musical imagery) the authors found, by comparing the three scan subtractions above, that:

- Semantic musical retrieval mainly involves areas in the right Frontal Lobe together with ‘secondary auditory cortex’ in the right Superior Temporal Gyrus.

- working musical memory mainly involves areas in the left Frontal Lobe

- the generation of musical imagery involves the Supplementary Motor Area

Several findings receive further discussion in the paper:

1) The discovery that auditory imagination ‘lights up’ auditory cortex has parallels with similar research showing that visual cortex ‘lights up’ during visual imagination. Both support “the hypothesis that cortical perceptual areas can mediate internally generated information”.

However, unlike visual imagination, during which primary visual cortex often ‘lights up’, this experiment only demonstrated activity in secondary [‘down-the-line’] regions of auditory cortex.

2) The finding that most brain activity during the imagination of familiar tunes was on the right side of the brain led the authors to conclude that “right-hemisphere specialisation extends beyond perceptual analysis to encompass complex tonal imagery processes”.

3) The right frontal regions involved in musical semantic retrieval are “approximately homologous” to the left frontal regions involved in verbal semantic retrieval, leading the authors to suggest that “the neural substrate of semantic memory retrieval may depend on the type of material to be retrieved”.

4) A brain area active in both imagery tasks is the Supplementary Motor Area (SMA), a region involved in coding movement. This, say the authors, “may imply a “singing to oneself” strategy during auditory imagery tasks”, perhaps “a subvocal singing or humming strategy during the generation process”.

5) The bias towards left frontal activity in the ‘Control/Image minus Control’ comparison leads the authors to speculate that “some of the areas activated in the left frontal lobe […] are related to working memory.”

Coda

Theme tune to “Dallas” (1978 US TV series)

Composer – Jerrold Immel