Title of paper under discussion

Music effects on event-related potentials of humans on the basis of cultural environment

Authors

Mehmet Kemal Arikan, Müge Devrim, Öznur Oran, Seniha Inan, Meyselon Elhih, Tamer Demiralp

Journal

Neuroscience Letters, 268 (1999) pp 21-24

Link to paper (free access)

(with thanks to The Institute for Music and Brain Science for the link)

Overview

Turkish participants, sporting electroencephalography (EEG) equipment to measure their brain responses, were each played a series of identical tones … with the addition of an occasional ‘oddball’ tone an octave higher, on hearing which they were asked to raise a finger. All the while, a track was playing in the background: either silence, white noise, a cello solo or a ney (reed flute) solo. On hearing the ‘oddball’ higher octave tone, a certain wave peak in the EEG readings called the P3 wave – associated with thought processes such as memory updating and selective attention – was noticeably bigger when the background track was the culturally familiar ney music, compared with the culturally less familiar cello, or white noise. Ney music didn’t just increase the size of the P3 wave – it also ‘moved’ it towards the front of the brain, compared to the P3 waves elicited with a silent background. This, in the words of the authors, “showed the effects of cultural environment on the cognitive processes”, suggesting the choice of music as a ‘cognitive enhancer’ needs to be culturally sensitive.

Method

10 participants, all academics at the University of Istanbul, were asked to wear EEG apparatus in order that the research team could measure the size and location of microvoltage electrical brain responses detected on the scalp. With the EEG monitoring in progress, each participant sat and listened to a series of identical tones (500Hz, which is a sharp-sounding B above middle C), interspersed with ‘oddball’ tones of 1000Hz (ie one octave higher). On hearing the ‘oddball’ tones they were asked to raise the right index finger.

Throughout the experiment different background tracks were played (at a quieter level than that of the tones): silence, white noise, cello solo (played by David Darling) and ney solo (played by Sadreddin Özçimi). All the participants had grown up listening to ney music – there had been a State monopoly on radio and television broadcasting in their childhoods, and Western classical music was off the State’s playlist.

Results

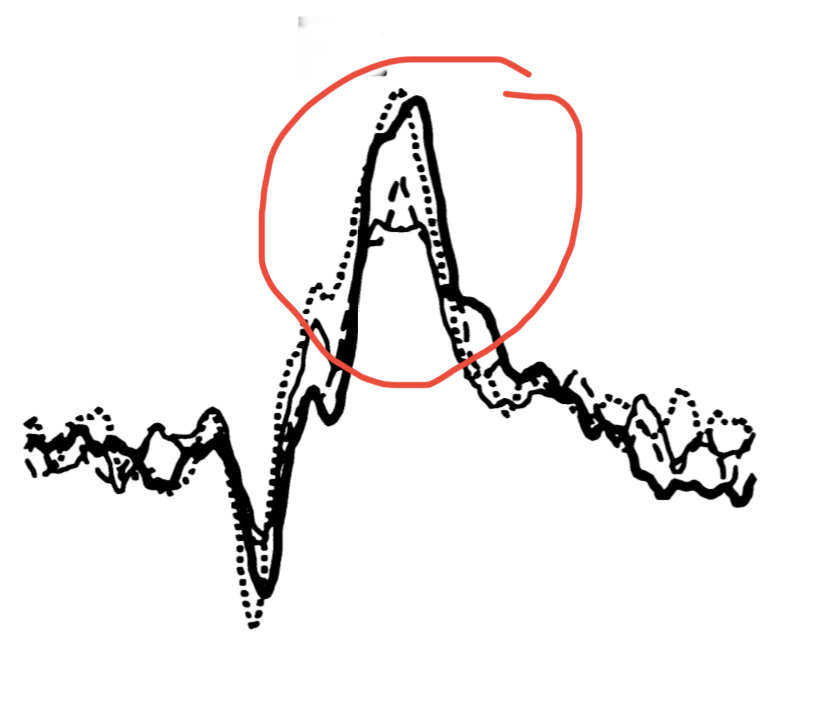

The scientists were specifically monitoring the EEG readings for the ‘P3 wave’, a positive spike in voltage detected on the scalp about 300ms after the presentation of the ‘oddball’ tone. Previous research suggested that the size and location of the P3 wave is not related specifically to the stimulus itself, rather the person’s reaction to that stimulus. The bigger the spike the higher the “allocation of attentional resources during memory updating processes” – in other words, the more thoroughly the ‘oddball’ event is being processed.

The first thing the scientists noticed was that the P3 response was greater during a background of silence or ney music than it was during a background of white noise or cello music:

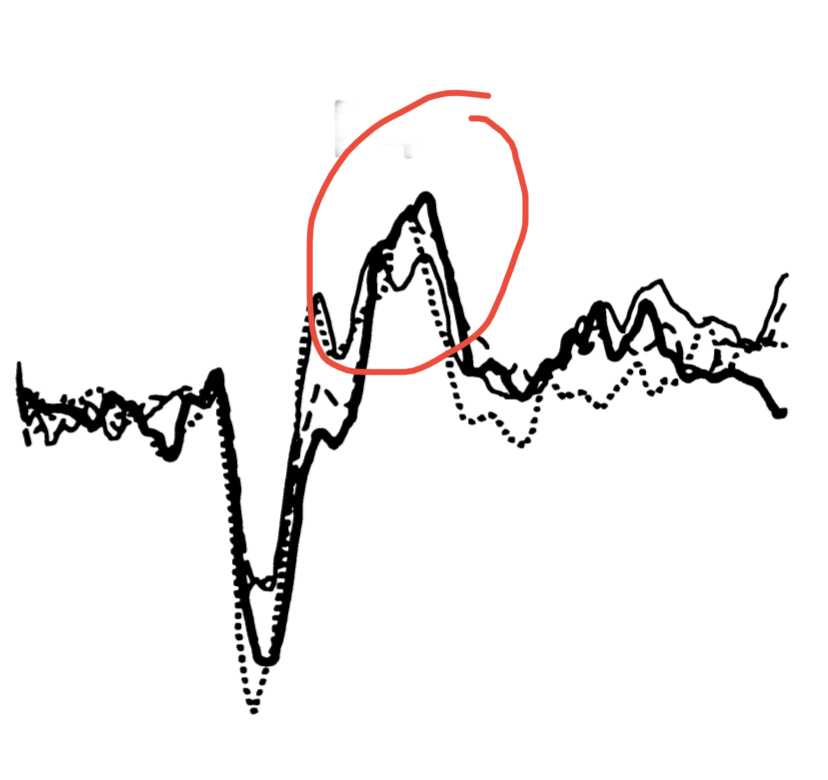

And secondly, although a silent background allowed for a strong P3 response, a ney music background allowed for an equally strong P3 response which was, in addition, more concentrated towards the frontal lobes of the brain:

Discussion

Interpreting an increased P3 response as a reflection of better “selective attention and memory updating”, Mehmet Kemal Arikan and his colleagues conclude that for their Turkish participants “ney music has a positive effect on these cognitive processes, whereas music played with violoncello does not.”

Furthermore they claim that “The relative increase of the frontal contribution to P3 with the effect of ney music might be considered a further finding supporting this viewpoint.”

They examined their data to see whether physiological arousal – elicited by familiar music – might indirectly account for such an increase in mental processing capacity, but neither their study, nor previous studies, suggested this was the case. They also measured the frequency spectrum of the ney music track compared with the cello track, in case that was the cause of the different P3 responses – but the spectra were too similar for that to be a responsible factor.

”Basically”, write the authors, “our findings suggest that transcultural study designs are needed to overcome the confounding factors emanating from the cultural environment of population. Otherwise, it seems that it is not possible to grasp the precise meaning of the data obtained by the studies on music effects on the electrophysiological parameters.” In other words, scientific studies in this area need to be sensitive to the cultural upbringing of the participants.

“Above all,” they continue, “this study suggests that music could be used either as a cognitive enhancer for certain psychiatric patients, such as the ones suffering from dementia, or as a supportive tool for certain psychotherapeutic interventions, such as cognitive psychotherapy. However, in order to reach this aim, it seems that one is obliged to take the cultural environment of the patient into account.”

Taking the quote ‘things learnt in early adulthood are remembered best’, the scientists conclude that the cognitive improvement in Turkish participants listening to the ney music of their youth demonstrates that “for older adults, the period from 10 to 30 years of age produces recall of the most autobiographical, the most vivid, and the most important memories.”

Coda

Ney – Sadreddin Özçimi