Title of paper under discussion

‘‘When the feeling’s gone’’: a selective loss of musical emotion

Authors

T D Griffiths, J D Warren, J L Dean, D Howard

Journal

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75:341–345

Link to paper (free access – scroll down to last two pages)

Overview

Are different brain areas responsible for handling music perception and music emotion? This case study, of a 52-year-old stroke victim, suggests the answer is yes. Before his stroke this patient consistently experienced ‘shivers down the spine’ listening to Rachmaninov preludes. After his stroke, he could still perceive music – its scales, contour, rhythm etc – but he was no longer blessed with an emotional reaction. Brain scans corroborated this state of affairs: permanent damage was revealed in a part of the brain known to process musical emotions – the left insula.

The patient

Before his stroke, our radio announcer would do night shifts at the studio, then come home and relax by listening to Rachmaninov. He described the Rachmaninov as music that induced an emotional “transformation”, described by the researchers as an “intense, altered emotional state”, a state he didn’t experience when listening to any other pieces of music or indeed in reaction to any other sensation.

In February 2000, he suffered a stroke, leading to a total loss of speech comprehension and output, and to paralysis on his right side. Within 12 months he had recovered amazingly, regaining total control of body movements and exhibiting only very subtle speech problems. But Rachmaninov no longer gave him shivers down the spine.

Clinical assessment

At an assessment in April 2001, the patient underwent ‘listening tests’, not just to determine his hearing ability but also his perception of prosody (intonation and stress in speech) and music. The music tests involved listening to a series of pairs of melodies (Melody ‘A’ and Melody ‘B’), and identifying after each pair whether they were the same or different. So, for example, in a given test Melody ‘A’ may be identical to Melody ‘B’. In another, Melody ‘B’ may differ in metre, and in another it may differ in melodic structure, or in rhythm. On evaluating the accuracy of his answers, the researchers were able to declare that his music perception was ‘normal’.

Structural MRI scans, however, were to reveal damage to the left hemisphere of the patient’s brain, especially to an area called the ‘insula’.

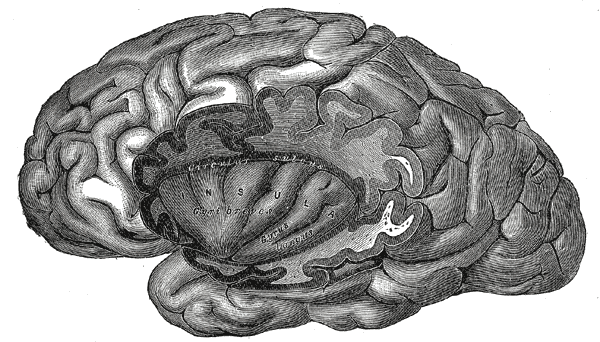

The insula in a healthy brain

Gray’s anatomy describes an expert brain dissection revealing the left insula – an area of cerebral cortex hidden deep in the temporal lobe – by cutting away the ‘lid’ (or ‘operculum’) of neighbouring cortex that overlays it:

Previous studies have shown the left insula, amongst other roles, is activated during an emotional response to music.

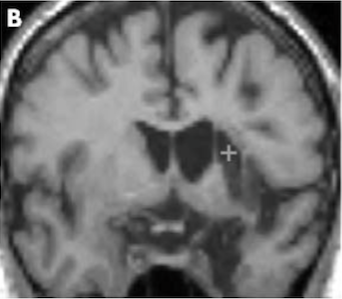

The insula in our patient’s brain

Here is a brain scan of our patient, on which the researchers have labelled the left insula with a grey cross.

The patch of brain tissue underlying the grey cross – including the left insula – is dark because it suffered permanent stroke damage. Note that the corresponding area on the opposing right hemisphere (the left-hand side of the scan as presented on the page) is light-coloured, meaning it’s healthy.

So it is revealed that our patient’s brain is damaged in exactly the area – the left insula – associated with emotional responses to music.

Discussion

This study, claims lead author Tim Griffiths, was the first to document a case of this sort, namely a patient who retained music perception but had lost ‘musical emotional processing’.

Importantly, one previous study had documented the opposite phenomenon, a patient whose ‘musical emotional processing’ was left intact after brain damage, but whose music perception was disrupted.

Taken together these two studies evidence a ‘double dissociation‘ between music perception and ‘musical emotional processing’. In other words, one patient exhibited music perception without ‘musical emotional processing’ and another presented with ‘musical emotional processing’ but with abnormally poor music perception. Such a double dissociation strongly suggests that music perception and ‘musical emotional processing’ take place in different areas of the brain. In the words of the authors, this supports the view that “functionally and anatomically separable neural networks mediate music perception and emotion”, adding that “The present study enables us to conclude that the left insula is involved in normal musical emotional processing of music.”

Coda

Prelude in G Minor, Op. 23 No. 5 – Rachmaninov

Yuja Wang – piano